|

By Jeanne Schoaff. Director of Programs, Museum of contemporary Art (MOCA) Fort Collins, Colorado. September 2007

Throughout time, war has been the subject of art. Homer’s descriptions of the Trojan War are studied by school children everywhere. Great novels by Tolstoy, Crane, and Hemingway describe war’s heroes and horrors. Museums, too, are filled with images of war and its toll on humanity. Our collective psyche has inherited the indelible images by Goya, Kolwitz, Sargent and Picasso of a succession of generational conflicts. There is neither surprise, nor joy, in discovering that the attacks on 9/11 and the current conflict in Iraq have become subjects for contemporary artists.

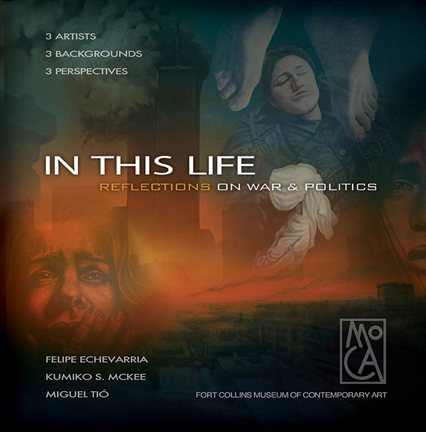

Kumiko McKee, Miguel Tio, and Felipe Echevarria reflect on the events of 9/11 and the war in Iraq from three personally and culturally diverse vantage points in the exhibition In this Life: Reflections on War and Politics. Kumiko McKee speaks profoundly to the emotions, which embrace or clash to create our culture of the present as well as individual experiences of those caught in the daily violence driven by the politics of the conflict. Visionary painter Miguel Tio’s spiritual perspective captures the humanity of souls passing on, and perhaps ultimately passing judgment. Felipe Echevarria’s surreal view of the destructiveness of war challenges us to reconcile current actions with our hope for the future.

Kumiko McKee’s precise, representational style uses old master glazing techniques combined with the Grisaille method. Using collage and tricks of perspective to compose narratives of the women and children caught in the crossfire of the war, the artist portrays the war as a personal and terrifying event. Her work captures the reality of war with gripping human emotions and incorporates elements with symbolistic meaning. McKee translates the effects of the political machinations of war into the personal consequences for the people living in the heart of the conflict. Her portrayal of the anguished faces of the Iraqi women and the child in Living in the Dead Zone creates a wrenching contrast to the idealism and patriotism suggested in Power on the Earth. The juxtaposition of impersonal political and military power against the visceral, highly personal outcomes of war prompts the viewer to consider the war from a variety of perspectives.

Born in the Dominican Republic, Miguel Tio lives in New York City and experienced first hand the attacks on the World Trade Center. Initially unable to paint after 9/11, Tio eventually experienced a spiritual vision of healing and peace. This vision compelled him to paint 8:30 A.M—a work that evokes the moments just before the first plane struck. While Tio’s classical style resembles that of McKee, he does not engage the viewer in overt political discourse. He focuses instead on a sacred interpretation of 9/11 and the events of the Iraq War, painting as he says, “not through eyes that are merely temporal, but through eyes which serve a higher purpose: as the windows of the soul.” The classical nudes and composition of The Journey After recall Michelangelo’s Last Judgment at the Sistine Chapel. The petty judgments of human discrimination, illustrated by orderly headstones versus unmarked graves, give way to an unconditional acceptance of all based on a singular and shared humanity.

The experience of war and destruction as a component of the human condition is central to Echevarria’s work. With images of bombs in mid-fall, and billowing black smoke obliterating a landscape, these compositions are devoid of humanity, but hint at the handiwork of human ingenuity. The lack of human participants intellectualizes and desensitizes the situation, echoing the average person’s detachment from events in Iraq. The viewer floats among the bombs drifting through a gorgeous sky, in My God Is Not Your God. The beauty of the intense color or startling composition, alongside the destruction of the narrative reveals the ongoing paradox of war and our relation to it. The juxtaposition of beauty and horror causes the viewer to contemplate both suffering and joy at once: the extremes of the human experience.

Taken together, the images in this exhibition address the complexities of religion, politics and life. The fact that humanity is capable of revenge, destruction and indifference, as well as forgiveness, courage and intelligence, has defined human experience throughout time and place. Echevarria, Tio and McKee—like other artists before them-- challenge us to learn and grow through conflict and crisis toward peace. The question remains: what we will learn, and how we will grow as a species?

|

In

This Life

In

This Life